What keeps the head of Ontario’s COVID-19 Science Advisory Table up at night

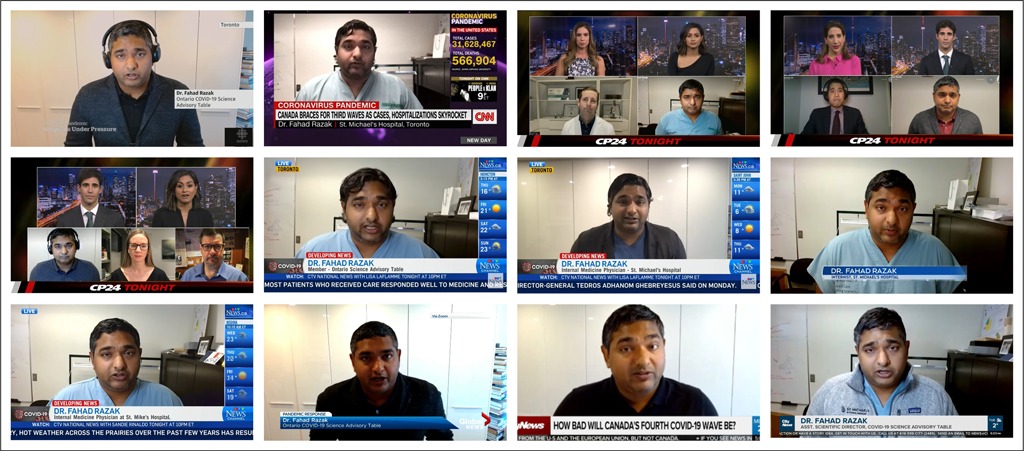

A conversation with Dr. Fahad Razak

Dr. Fahad Razak, clinician-scientist at St. Michael’s Hospital, had a tough decision to make. As a physician, the past two and a half years have been the busiest of his clinical career, caring for the sickest patients with COVID-19 when they are admitted to hospital. All the while, he’s co-led a big data research program, continued investigating and publishing studies and contributed to Ontario’s COVID-19 Science Advisory Table as a member and then assistant director. And as a dad of two young children, being there for his family remained his top priority.

So when he was offered the chance to lead the table as scientific director, he knew something had to give if he was going to be able to give Ontarians his all.

We spoke with Dr. Razak about his decision to step away from clinical practice while taking on this role, who should get their fourth dose and why ‘the overlap’ of four separate issues has him concerned for the fall.

What’s a day in the life like for you as director of the Advisory Table?

We tend to have a lot of meetings early in the day that set the direction for what we’re working on. We have leadership huddles where we review the major topics we’re focusing on and look at how well they’ve progressed, and discuss when to present them to the table, when to publish them or when they can be released to government and other stakeholders. It’s also an opportunity to discuss any of the fast evolving changes in the pandemic. One of the most remarkable things to me is that you can think you understand something in the morning, and then you’ll have to completely reevaluate your position by the afternoon. That’s just the nature of how fast things are changing.

A lot of the meetings later in the day are either meetings with our scientific partners – members of the table who are developing briefs on various topics such as therapeutics, public health strategies, vaccination rollouts – or it could be meetings with people from the ministry, public health officers, business leaders, or members of the government who have to take some of our work and think about the implications.

And then a lot of my day is consumed with the media interviews and speaking to the public. A big part of this role is communications – as the director, I need to take the ideas and the work of the table out to the public and tell them what we’re seeing and thinking. This has been a scary couple years for Canadians and we see our role on the table as being an honest and transparent voice about what the science is showing, what we know, and importantly, what remains unknown and potentially of high risk. One of the big challenges for me is to communicate the difference between science and policy – science is what we are seeing and what could happen, policy is what we should do as a response – and those are the big, difficult decisions that elected officials need to make.

Will you still be treating patients at St. Michael’s while director of the Science Advisory Table?

When I was offered position of becoming the new director of the table, I realized it wasn’t something that I could do at same time as all the other things that were important to me and that I was committed to. I’m a general internist, so that means I care for patients that are hospitalized with severe medical ailments. To put that into context, general medicine is the largest part of the hospital. It cared for about 40 per cent of all hospital admissions even before the pandemic began, and it’s been the medical service that cared for at least 80 per cent of all hospitalized COVID patients in the first two years of the pandemic.

For me what that meant is clinically these past two years have been extremely busy, it’s been the most clinical work I’ve ever done in my career and it really exposed me to the worst of this disease.

I also co-lead a large research group – GEMINI – that has almost 40 employees and many students and trainees, and I wanted to make sure that part of my career continued to flourish. And with two young children at home, I want to be there for them and my wife – they are my highest priority.

So stepping into this role meant giving something up. And for me right now that meant clinical work – the plan is to step away for a year and then reevaluate. The whole reason I got into medicine in the first place was to care for patients, but right now I’m going to dedicate myself to best supporting the table to meet the needs of the province.

Eligibility for fourth doses of the COVID-19 vaccine has expanded in Ontario. Who should get their fourth dose?

I’m going to start by saying that I want to make sure in the conversation around fourth doses that we don’t miss out on the fact that only about half the people in this country who are eligible have received a third dose. There is no scientific debate about whether a third dose is beneficial. It is beneficial not only to provide protection in the short-term, but it seems to give you durable protection against severe disease, like ending up in hospital, ICU or even dying from COVID-19. This is huge missed opportunity – to get third doses – has not been taken by millions of people across country.

Now to your question – there are groups for whom a fourth dose is a pretty clear win, and who should have already taken it. If they haven’t, they should go get it now. That includes the elderly, people who are immunocompromised, and people who have other high risk exposures like living in long-term care or congregate settings. For them, the fourth dose it not only protective against mild infection and transmitting infection, but it’s also been clearly shown that it protects against severe disease.

For those who are under 60 and otherwise healthy, the benefit of a fourth COVID-19 vaccine dose sounds marginal. Why should those people get their fourth doses?

Someone under 60 who is otherwise heathy and has had three doses should ask themselves: Does your work put you in a position where you’re being exposed to a lot of people, especially with limited protection or in a higher-risk setting like indoors with poor ventilation? Or maybe you live with or are close to someone who is very high-risk if they get exposed through you. Also, the effects of infection may be very disruptive for your life, even if you don’t get hospitalized, such as missing a week of work or school. Finally, how long has it been since you received a third dose, or were infected? If you are approaching six months or longer the case becomes stronger.

My advice to everyone is get the vaccine dose you’re eligible for, especially if you haven’t had a third dose, and for the high-risk groups I described, get a fourth dose. For everyone else, if you want to feel more confident about your protection please go get it. But for everyone, regardless of vaccine status, don’t forget about the other non-vaccine related public health measures that work like masking, increased ventilation, reducing exposure risk, using rapid tests before you meet with friends, and not going out if you feel sick. And know that this is probably not the end of vaccination, we’re gearing up for renewed vaccination in the fall or early winter and more may be on the horizon.

What are your predictions going into the fall?

Early in the pandemic we used to be able to look at other countries with a much greater ability to take lessons about what to expect here – they were often weeks or maybe a month or two ahead of us in pandemic waves. It has become harder and harder to draw lessons from those countries because every country now has different levels of immunity and different patterns of vaccination.

Waves of COVID-19 surges are now occurring every three to six months, so there’s a very high likelihood that we’ll see another wave. We don’t know the amplitude or the variant that will drive it, but there will likely be another wave in the fall and winter. That’s also a traditionally challenging time for other respiratory viruses like the influenza, and we’re seeing some signals from the Southern hemisphere that this could be a bad influenza season.

Is there anything that keeps you up at night?

I worry a lot about how much more our health system can give. In my career, I’ve not seen the system so stressed or frankly broken as it is right now. We asked an incredible amount of our frontline healthcare workers, public health infrastructure and healthcare and public health leaders to manage the early waves of COVID-19.

At the same time, the public is also exhausted with pandemic control measures. A good example to demonstrate this is our third dose vaccination rates. Unlike the first two doses where we were the lead among comparable wealthy countries, we have slipped to very much the middle of the pack in our third dose. That reflects the fatigue of the public. And gaps in our messaging to them about what is required now to protect yourself.

The thing that really worries me is the overlap between a health system that’s running on fumes, the potential resurgence of non-COVID respiratory viruses like RSV and influenza, another COVID-19 wave, plus fatigue in the public for the steps that are required to manage and control the pandemic. That is the nightmare scenario.

What makes you feel hopeful?

Let me start with the science. Despite some of the losses in immune protection we are seeing in symptomatic illness, we are still seeing very good protection against severe disease. So in this wave, although we’ve had a rapid rise in cases and hospitalizations, we have not seen a rapid rise in ICU admissions or deaths. It could be because we have lingering immune protection from vaccinations or from infections over the past six months. It that continues, it may mean we’re starting to develop some level of population immunity, at least against severe disease – that’s a good thing.

The other thing that gives me hope is we finally have a vaccine for under five year-olds. This has remained our big vulnerable group – including my children – and we finally have a mechanism to give them some protection against the virus.

And lastly, the Canadian public and people of Ontario proved that they were able to rally around public health messages, for example going to get vaccinated, and I think they will follow that again if we on the public health side can clearly articulate what is needed. I think people will do their part to protect themselves, each other and our health system.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

By: Jennifer Stranges