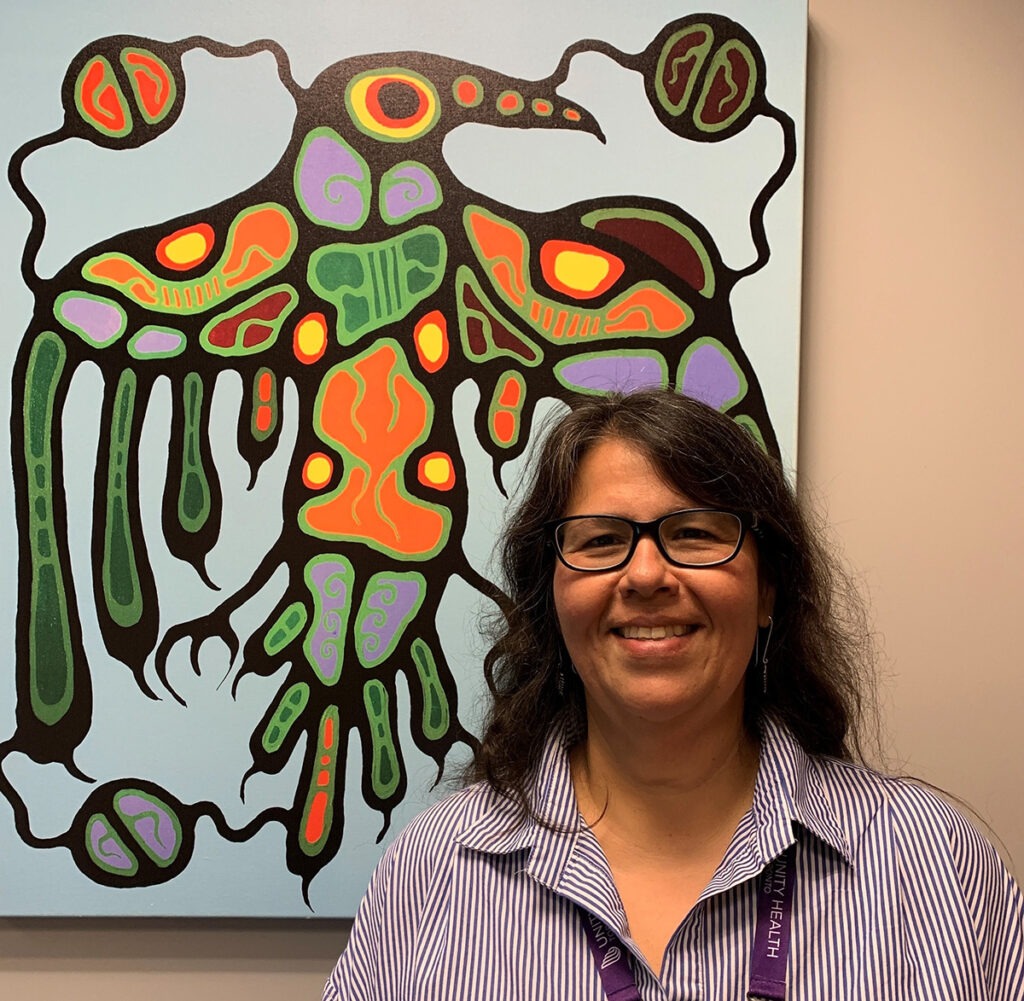

Meet Roberta Pike, the inaugural Director of Indigenous Wellness, Reconciliation and Partnerships at Unity Health Toronto

Sign up for the Unity Health Toronto newsletter, a monthly update on the latest news, stories, patient voices and research emailed directly to subscribers. If you haven’t subscribed yet, you can do that by clicking here.

Over the last decade, Roberta Pike has heard countless stories from Indigenous patients of the injustices they experienced while receiving care in a hospital-based setting. So, she set out to help fix the system.

“These issues of justice, of anti-Indigenous racism and of poor care really upset me,” she says. “I wanted to find a way to work closely with large institutions to address these issues, help them better themselves and hold them accountable for delivering culturally safe and competent care, which is a human right.”

Now, as the first Director of Indigenous Wellness, Reconciliation and Partnerships at Unity Health Toronto, Pike is looking to support the organization in its efforts to advance Indigenous health and reconciliation. Her role is the first of several new Indigenous Wellbeing team members who will co-lead this important work with Unity Health leaders and the Indigenous community.

We sat down with Pike, Anishinaabekwe from Henvey Inlet First Nation, to learn more about her new role and what else she’s learned over her 33-year career in Indigenous health.

What drew you to this role?

There are two things that Indigenous people often think about. The first is our spiritual name and what it means, which tells us our purpose in life. The second is our clan; each clan is given a different responsibility. My spirit name is Na’w ode’ giizhigokwe, which translates to Centre Heart Sky Woman. There’s a long teaching behind my name but distilled down, my purpose in life is to centre my heart and mind to provide effective leadership. My clan, Waabizheshi (Marten), are the warriors, peacekeepers or strategists in our clan system. We look for ways to make sure that the community’s needs are met, to ensure survival, but also to establish and maintain good relations with others. I look at this role as furthering my responsibilities and purpose in life.

This role marks the progression of Unity Health’s Indigenous wellness, reconciliation and partnerships human resources strategy. Last year, we announced Dr. Janet Smylie as the Strategic Lead of Indigenous Wellness, Reconciliation and Partnerships, helping to lay the foundation of this strategy to advance Indigenous health and reconciliation. What does this strategy look like and why do we need a human resources strategy for the network?

At the simplest level, this is a targeted strategy to hire more Indigenous people in key positions across the organization. Indigenous people have some of the worst health outcomes, stemming from significant barriers to health care, including a lack of trust in – and fear of – the health care system. Indigenous care providers have an automatic connection with Indigenous patients; they understand the barriers to health care, the trauma and discrimination they may have experienced and how to provide care in a safe and culturally competent way. The respectful inclusion of Indigenous language, culture and ceremony are strengths and protective factors that aid in the healing process. To feel comfortable in our care, Indigenous people need to be able to see themselves represented in our work force.

Allies are also important. When Indigenous patients present with chronic illnesses, there can be a deeper pain or inter-generational traumas beneath the presenting symptoms. Indigenous peoples are resilient, despite the horrific colonial experience. When they come to us (those who they trust the least) for care, we need to be highly attuned to their needs and concerns. As an organization, we need to do a better job of educating staff and physicians on the true history of Indigenous relations in this country and how to deliver and ensure a meaningful care experience for Indigenous peoples.

This recruitment plan, which is being developed with the First Nations, Inuit and Métis Community Advisory Panel at Unity Health, aims to bring in more Indigenous staff for a specific subset of roles to help advance Indigenous health and change across the organization.

Do you have any specific goals or priorities in your first few months in this role?

One of my first priorities is to explore the use of Indigenous-identifying information in Unity Health’s new electronic patient record system. We need to address how ‘Indigenous’ gets used in the system, what it means, who has access to this information and for what purposes. More broadly, I’ll be working on a corporate response to how Indigenous-identifying information gets used within the organization.

Another priority of mine is to meet as many people – security, leaders, clinical staff, corporate staff, porters, volunteers, physicians, learners and of course, Indigenous patients – as possible across the organization. These relationships will help me understand how I can assist various groups, where we might be falling short on supporting Indigenous people and where we’re providing exceptional care. I also want to identify ways to improve professional development and learning opportunities for staff and physicians. I want everyone at Unity Health to feel free to approach me to discuss Indigenous health and I want to spend my time investing in building reciprocal relationships.

I also plan to take a retrospective look at our relations with Indigenous people. Our history tells us a lot about our future; uncovering the truth about our past relations helps us address those harms and develop a strategy that recognizes the needs of today and seven generations into the future.

Before joining Unity Health, you were the Executive Director of the Toronto Birth Centre, a unique space operating from an Indigenous framework where pregnant people in the care of midwives can labour and give birth. Prior to that, you worked in the Ontario Public Service, managing portfolios including the Indigenous Healing and Wellness Strategy. What compelled you to work in these spaces and why is it important to have Indigenous leadership at the helm of these efforts?

I was raised in two worlds, straddling the Indigenous and mainstream societies. As a young child, I saw the inequity in being born an Indigenous female in this society and it really upset me. My parents understood how my identity needed to be fostered through contact with and immersion in my culture, language and traditional teachings, to counteract these external influences. I knew early on in life that I wanted to make a difference, to be a leader and improve the lives of those in my community.

To make changes to Indigenous health and wellness, we need to help people where they’re at and where they want to be. Who understands Indigenous peoples better than Indigenous people? We’re familiar with the racism, discrimination and past traumas, as well as our culture and ceremonies, which are important for healing. There’s a place for Western medicine and there’s also a place for Indigenous medicine, spirituality and ceremony. Offering both – and knowing how – is important. Indigenous people have a right to self-determination; to control their own futures, as individuals and as a collective. Unity Health’s Indigenous Health Strategy is rooted in the concept of ‘Nothing About Us, Without Us’.

You’ve previously lectured on growth, development and serving Indigenous populations, as well as culturally safe and competent care. What are some solutions or changes that health care workers can make to ensure that they’re providing culturally safe and competent care?

The best thing that anyone can do in this work is be humble. It doesn’t matter if you have experience working with Indigenous patients or you have Indigenous friends, there’s always more to learn. We need to recognize where our internal biases are and keep ourselves open to continuous learning. Subconscious biases are hard. You might think that you’re an ally but then you inadvertently say something harmful. If that happens, we need to acknowledge it, explore the roots of it and replace those thoughts, values or beliefs with something new. It takes time to break the bad habits that colonization has ground into all generations; we need to commit to putting in the work every day.

Where do community partnerships come into play in this new role and why is collaboration, particularly with Indigenous people and communities, so important for advancing Indigenous health and reconciliation?

My role taps into three focus areas and one of them is partnerships. St. Joseph’s Health Centre and St. Michael’s Hospital see some of the highest rates of Indigenous patients in the city. As we consider our efforts towards Indigenous wellness and reconciliation, we need to look beyond the hospital walls. Every patient comes to us from somewhere, and after they leave the hospital, they’ll return back to that setting or community. Partnerships are key to bridging the care that Indigenous people receive in hospital with the continuing care they receive in the community. If the partnerships are strong, patients are less likely to return to hospital in even worse condition. I’ll be looking to build strong relationships across the organization and partnerships within the community, to develop safe service pathways.

I’ll also be looking to develop ongoing relationships with other Ontario hospitals that have Indigenous programs. We’re not the only organization engaged in doing this work and there’s so much we can learn from each other. The purpose of community is to support and care for one another; it’s not a competition.

You’ve been an active member of the First Nations, Inuit and Métis Community Advisory Panel (FNIM-CAP) at Unity Health for about six years. What have you learned in this membership role that you’ll be carrying into your new role at Unity Health?

The biggest lesson I’ve learned is patience. This work isn’t easy and it takes time. There have been many moments where I’ve felt tired but I didn’t give up. I continued to show up, to come to meetings and to push the organization to recognize the importance of the work that we’re trying to do.

When you sit on the FNIM CAP, you wear many hats – you’re a patient, caregiver, family member, staff or community member. Getting to work with so many different people and roles has exposed me to different parts of the organization, which has been helpful for identifying where we can do better or have an impact.

I’ve also gotten to know the senior leaders at Unity Health, and I can see how truthful and honest they’ve been. They recognize where the hospital has fallen short, they listen critically to the needs identified by the Indigenous community and they honour Indigenous-led recommendations for a path forward. I think that’s one of our strengths – the respect for the Indigenous community and willingness to invite them to be a partner – and have control – in the direction of the types of change we need to make.

Do you have any advice for those who want to learn more about Indigenous history and culture or who want to help build and repair relationships but are afraid of offending others?

One of the best things that people can do is take the San’yas Anti-Racism Indigenous Cultural Safety Training Program. It’s a valuable learning experience and I’m hopeful that everybody at Unity Health will complete it. I also encourage people to embrace their discomfort and find opportunities to discuss their learnings with others, whether members of my office, in their personal circles or beyond. We can’t learn and grow without opening ourselves up to our vulnerabilities. There’s an organization called Circles for Reconciliation, that’s doing deeper reconciliation work. They provide a 10-week opportunity for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people to participate in facilitated conversations, with the goal of building respectful relationships towards reconciliation. I encourage everyone to investigate options that exist for safe learning and growth.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

By: Anna Wassermann