From the front lines: How Unity Health Toronto experts are helping Canada’s health system prepare for emergency events

In the early 20th century, in the midst of the First World War, a physician at St. Michael’s Hospital did what had previously been unthinkable: he replenished an injured patient’s blood supply by transfusing them with blood from another person.

A plaque commemorates this significant “Canadian first” on Bond Street, just outside an entrance to the hospital. It memorializes a blood transfusion in 1917 that shaped medicine for patients in Toronto, across Canada, and on battlefields around the world.

Canadian physicians and researchers continue to play pivotal roles in shaping wartime medicine. Our country’s leading minds are driving innovation to save lives and improve rehabilitation for wounded soldiers. St. Michael’s Hospital, a site of Unity Health Toronto and one of only two American College of Surgeons-verified Level 1 trauma centres in the country, is integral to that work.

Now, over a century later, attention is turning away from history and toward conflicts of the future.

Enjoying this story? Sign up for the Unity Health Toronto newsletter, a monthly update on the latest news, stories, patient voices and research emailed directly to subscribers.

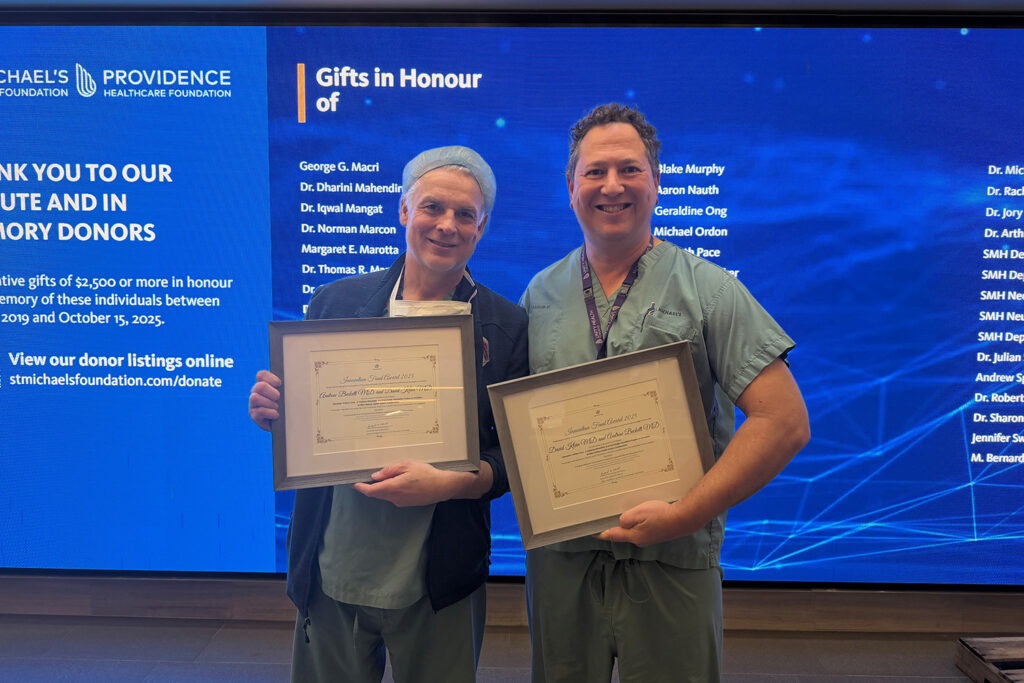

In 2024, Dr. Andrew Beckett, a trauma surgeon and scientist at St. Michael’s and Chief of Trauma in the Canadian Armed Forces, and Dr. David Klein, a critical care physician and scientist at St. Michael’s, teamed up with the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto, the Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research, Canadian Forces Health Services, and the Canadian Joint Warfare Centre to hold an emergency preparedness training exercise.

The exercise, called Trillium Cura, mapped out what would happen if a war broke out in Europe involving NATO countries. Could Canada support a sustained flow of casualties? Could we keep up with the demand for blood products, antibiotics and surgical tools?

This year Beckett and Klein took their interest further with a pan-Canadian training exercise called CANADA PARATUS, hosted at the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute at St. Michael’s, exploring a scenario in which Russian drones entered Poland, triggering a NATO response. The result was massive and instantaneous: more than 100 casualties were sent back home every week for care.

The goal of these exercises is to improve preparedness, awareness and understanding of how civilian and military health systems have to work together to respond to complex emergencies.

“None of us wants anything to happen,” says Beckett. “But we want to work together with the military and St. Michael’s Hospital to improve the resiliency of Toronto-region health care and be as prepared as possible at the provincial and federal level in case something does.”

For Klein, the hope is to start “building bridges and lines of communication around readiness and preparedness, whether it’s war or any other disaster we must face as a nation.”

Military conflicts tend to result in specific health care needs, and by extension specific areas of interest for research and innovation: resuscitation, bleeding and wound management, burns, prosthetics, transfusion, and even artificial intelligence. St. Michael’s Hospital has expertise in many of those areas.

Supporting Beckett and Klein’s call for increased preparedness, Dr. David Gomez, a trauma surgeon and scientist at St. Michael’s, recently published a paper examining the resiliency of the Ontario health care system to care for casualties of a conflict with a near-peer adversary. In simple terms: if Canada had to support the evacuation of and care for large numbers of military personnel and civilians with complex, traumatic injuries, would our health care system hold up under the pressure?

The paper showed that there are currently 168 adult acute care hospital sites with 21,000 beds in Ontario, supporting a population of almost 16 million. Seventy-four of those hospitals have intensive care units, 9 are designated trauma centres, and two have adult burn units. There are 11 stand-alone rehabilitation hospitals in the province, and other rehabilitation units exist within acute care hospitals.

Using the Ukraine-Russia conflict in Europe as a guide, as well as historical examples from other conflicts, the paper showed that at the peak of a conflict, trauma centres might see anywhere from a three to 25 per cent volume increase, while rehabilitation centres could see up to 37 per cent increases.

“A system-wide response would be required in order to generate additional ward and ICU capacity at trauma centres,” the study reads. “We must identify and plan which areas of scheduled and urgent care would be transitioned from trauma centres to the rest of the system while still guaranteeing access to timely and quality care for the civilian population.”

Unity Health Toronto’s military collaborations go beyond disaster-preparedness. In July, a group of CAF medical professionals, including a doctor, paramedics, nurse and physicians’ assistant, visited St. Michael’s Hospital for its annual Emergency Skills Day. Along with residents and medical professionals from the hospital, the contingent of CAF health care providers used Unity Health’s state of the art Simulation Centre to practice clinical skills and emergency scenarios.

Alexander Beaton, a Nursing Officer and Major in the CAF, says the forces often rely on civilian partners to maintain and hone clinical skills. His team has rented out the Simulation Centre a few times for hands-on trauma and surgical training.

“Our paramedics and combat medics are responsible for practicing in quite an unpredictable environment,” says Beaton. “Days like skills day are great for practicing chest tubes, needle decompression and difficult airway management.”

In return, civilian medical professionals learn from their CAF counterparts about working in many challenging conditions, from having very little light to relatively few supplies. The Canadian military, as Beaton says, operates a whole health system, from public health to primary care and trauma medicine. They have a lot of wisdom to share.

As Klein puts it, “For better or for worse, the history of medicine and the history of war are inexorably linked.”

By Olivia Lavery