‘Game changer’: Canadian scientists develop blood test to quickly predict risk of sepsis

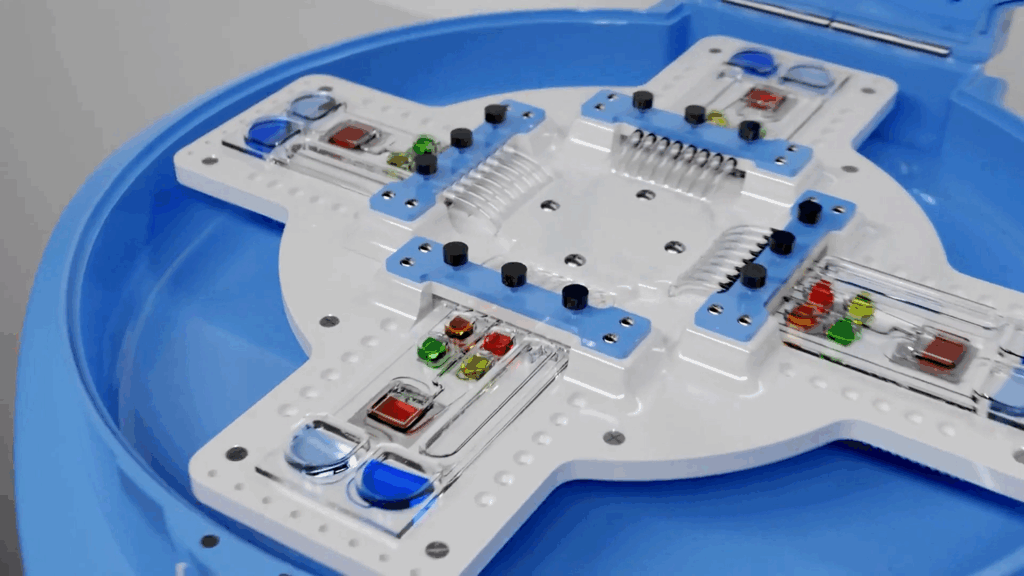

The PowerBlade device is pictured. (Photo: National Research Council Canada)

A team of scientists from across Canada has developed an innovative molecular-based blood test and portable device to quickly predict the risk of sepsis over the first 24 hours of clinical presentation.

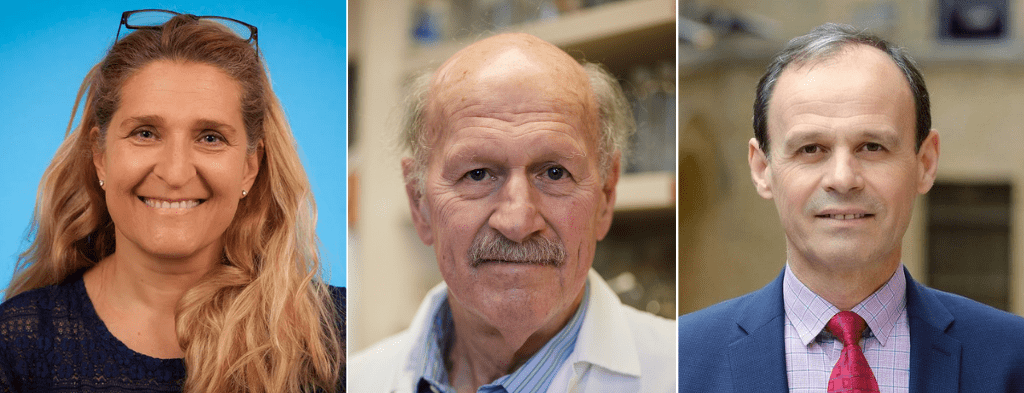

A research paper describing the test and its development was published in Nature Communications. It represents a major milestone in the way doctors will evaluate and treat sepsis. The study was the result of a collaboration between three multi-disciplinary teams. Dr. Pamela Plant and Dr. Claudia dos Santos at St. Michael’s Hospital/Unity Health Toronto, Dr. Robert Hancock at the University of British Columbia and Dr. Peter Zhang at Sepset Inc., and Dr. Lidija Malic and Dr. Teodor Veres at the National Research Council of Canada’s (NRC) Medical Devices Research Centre.

Enjoying this story? Sign up for the Unity Health Toronto newsletter, a monthly update on the latest news, stories, patient voices and research emailed directly to subscribers.

Sepsis is the body’s extreme and dangerous reaction to an infection. It happens when your immune system, instead of just fighting the infection, goes into overdrive and starts attacking your own organs and tissues. This can lead to serious problems like organ failure and death if not treated quickly.

The problem is that it is very hard to predict who will develop sepsis. Many people get infections, but only some go on to develop the full-blown sepsis syndrome. Right now, there’s no perfect way to tell which patients will get worse. This makes it challenging for doctors to catch it early and start treatment before it becomes life-threatening.

“Sepsis is a major killer globally, affecting 49 million people each year, with an estimated 11 million deaths. This represents roughly 20% of all global deaths. In Canada, sepsis is responsible for approximately 18,000 deaths annually, with 75,000 new cases occurring each year,” said Dr. dos Santos, St. Michael’s Hospital critical care physician, scientist and study lead author. “Our hope is that our test will be a powerful game changer in preventing sepsis deaths, allowing physicians to quickly identify and treat patients before they begin to rapidly deteriorate.”

Current diagnostic tests have poor ability to identify patients at risk of sepsis. In addition, they are still performed in centralized labs, which require specialized equipment and staff, making them slow and inaccessible for many vulnerable patients. This “bottleneck” means delays and every hour sepsis goes undiagnosed increases the chance of death by nearly 8%. Being able to quickly identify which patients are at risk is a major public health advancement, said dos Santos.

The Sepset blood test

The research team examined blood samples from 586 hospital patients with suspected sepsis. Using machine learning (a type of AI), the team identified six key genes that show changes when the body’s immune system is starting to dangerously dysregulate. Identifying this six-gene signature – called “Sepset”—in the patient’s blood was key to predicting whether their condition would worsen in the first 24 hours.

The test was validated in 3,178 patients. A version of the test applied to 248 patients, using the common lab technique called RT-PCR, was 94% accurate in detecting sepsis patients whose condition was about to worsen.

“This demonstrates the immense value of AI in analyzing extremely complex data and both identifying the important genes for predicting sepsis and constructing an algorithm to accurately predict if a patient is at risk from this deadly disease, sepsis,” said Hancock, University of British Columbia Killam professor, Director of the Centre for Microbial Diseases and Immunity Research and CEO of Sepset.

To bring this diagnostic capability closer to the bedside, the NRC developed a portable, microfluidic-based platform called PowerBlade. This core technology integrates multiple steps—RNA extraction, amplification, and detection—into an automated, miniaturized workflow that can be performed at the point of care using less than 50 microliters (roughly a pinprick) of blood.

The field-deployable version of the test implementing a digital droplet PCR method, called PREDICT-PowerBlade, was 92% accurate in identifying patients at high risk of sepsis and 89% accurate in ruling out those not at risk. It delivers results in under three hours and is designed to function without the need for complex lab infrastructure or highly trained personnel. This performance brings a powerful new tool into the hands of frontline healthcare providers, where speed and accessibility can make the difference between life and death.

The availability of such a portable device will be critical in enabling treatment to be provided whenever and wherever a patient may be, whether that’s in the emergency room or in a remote Northern community, said Hancock. The team is also working on making the test faster, with the expectation that in the future test results will be available in less than an hour.

(Photos: National Research Council Canada)

Dr. Teodor Veres, of the NRC and co-director of the Centre for Research and Applications in Fluidic Technologies (CRAFT) adds, “By combining cutting-edge microfluidic research with interdisciplinary collaboration across engineering, biology, and medicine, CRAFT enables rapid, portable, and accessible testing solutions.” CRAFT is a joint venture between the University of Toronto, Unity Health Toronto and the NRC. This collaborative approach accelerates the development of innovative devices that can bring high-quality diagnostics to the point of care, transforming how we detect and manage critical conditions like sepsis.

With the Sepset test and PowerBlade platform, Canadian researchers have created a novel, accessible solution that brings precision diagnostics to the frontlines of care—whether in urban hospitals, rural communities, or off-planet environments. It represents a promising leap forward in the effort to reduce the global burden of sepsis and improve patient outcomes through earlier, more effective intervention.

By: Marlene Leung