Code Orange: How the St. Michael’s Emergency Department prepares for an external disaster

Imagine there’s been a blast at Pearson Airport with reports of multiple people injured and deaths. St. Michael’s Hospital, one of a few Level 1 trauma centres in Ontario, has received word that 24 patients are headed to its busy Emergency Department (ED). The ED team springs into action, initiating a Code Orange – the hospital-wide alert for an external emergency. Frontline ED staff prepare and decant the unit, making space for a surge of new patients. As the injured arrive, triage staff allocate spaces based on the severity of their injuries.

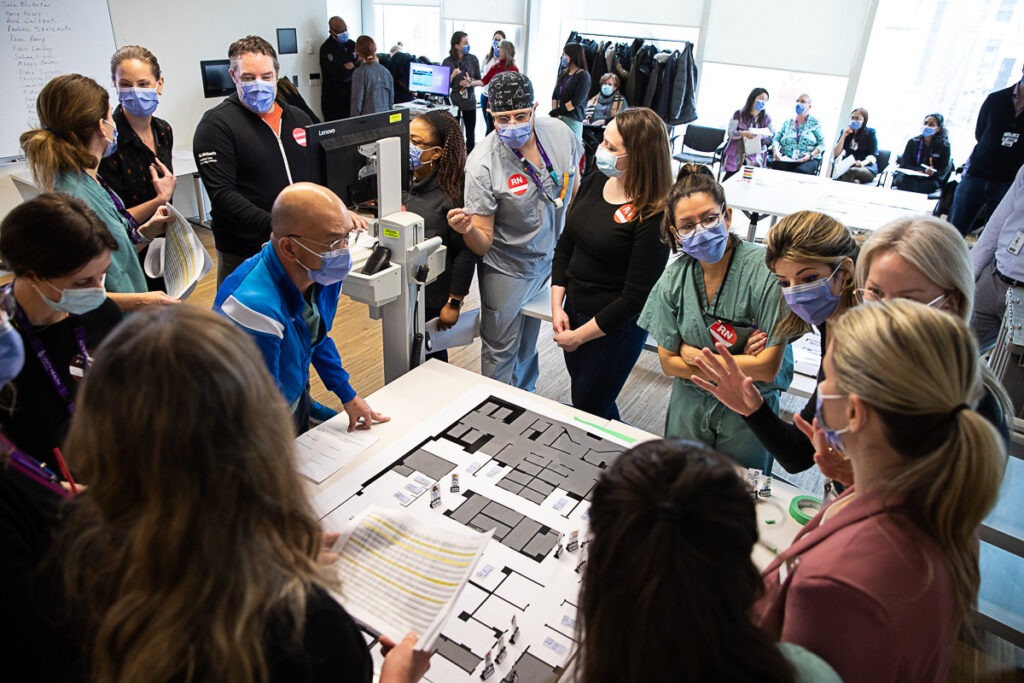

This simulated scenario was the basis for a recent Code Orange tabletop exercise at St. Michael’s Hospital. These exercises, which involve ED staff, physicians, hospital administrators and stakeholders from other departments, are designed to assess and improve the hospital’s preparedness for when real-life external emergencies take place.

“Mass casualty events are one of the most challenging situations an ED will face,” says Emergency Physician and Trauma Team Leader Dr. Rachel Poley. “It is important that we test and practice our protocols, so we can continue to improve and be ready to care for the patients who need us. We must practice these exercises regularly to stay on top of our game.”

St. Michael’s Hospital played an important role in caring for the injured in the 2019 Raptors Championship parade and the 2018 Danforth shooting. As one of only two Level 1 adult trauma centres in Toronto and one of nine in the province, the hospital has a responsibility to make sure it’s prepared for when the next incident happens, Poley said.

“These exercises are integral to us feeling a sense of control when a mass casualty event occurs,” she said. “Among the chaos there is power in knowing what you are supposed to do. This serves our patients well, and makes us proud to work at St. Michael’s.”

Something new every time

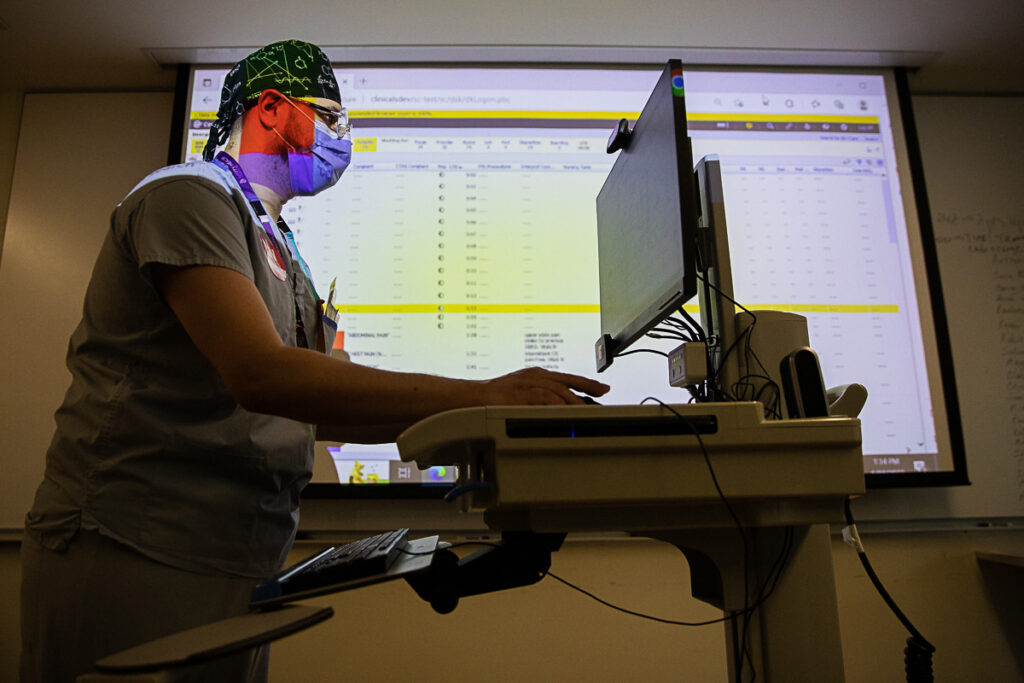

Poley and her team spent more than three months planning all aspects of the tabletop exercise, from creating the scenario, writing simulated patient profiles, and mapping out hospital bed occupancy levels and resources. They used data from the ED to make sure the scenario mirrored typical conditions in the hospital.

“We try to make these scenarios as realistic as possible,” Poley said, noting that the inspiration for the exercise was a recent evacuation at Billy Bishop Airport due to a possible explosive device that turned out to be a false alarm. “We played off that event. An explosion also creates unique injuries that involve both penetrating and blunt injuries, and allows us to run through a breadth of clinical scenarios that require specific resources.”

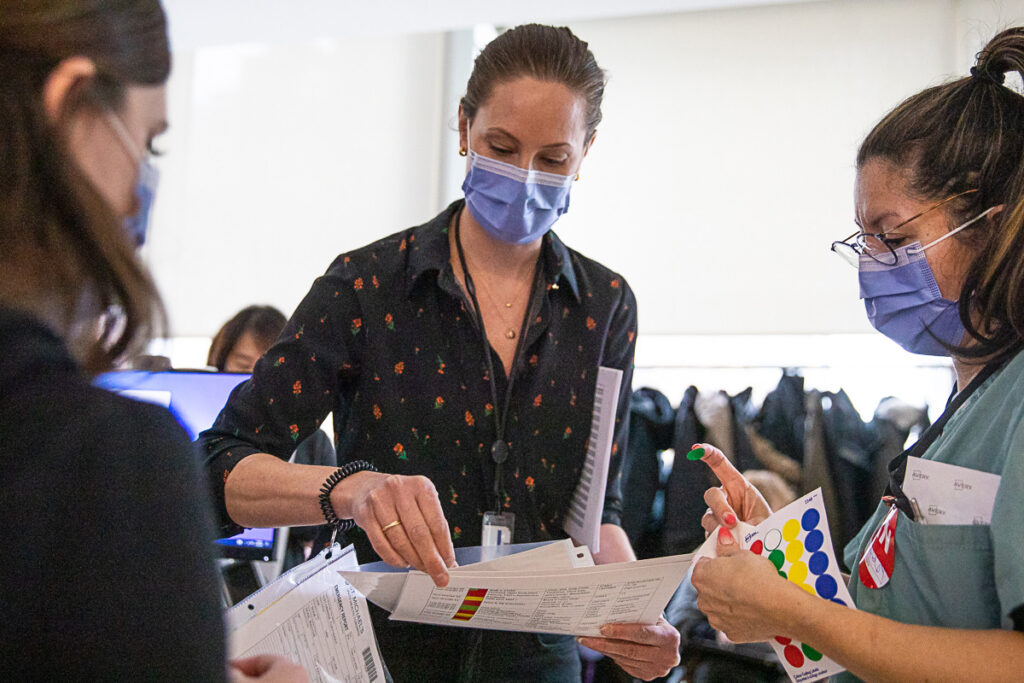

During the exercise, Trauma Program Manager of Registry Amanda McFarlan stands in line to be registered as a patient. “Hello, I’m patient 49,” she tells registration staff as she reads off a card containing her patient profile. “I have shrapnel in my abdomen, I’m awake and alert and I’m on a stretcher.”

McFarlan says that every time the team conducts a Code Orange simulation they discover something about their processes that could be improved.

“It could be something as simple as, ‘Oh, that box we need is under a big pile of heavy stuff, so it should be moved,’” she said. “Or it could be figuring out how to quickly register a whole bunch of people with similar injuries without mixing them up.”

The last time the ED held a Code Orange exercise, the team saw that there were inefficiencies during the registration process and refined them afterward as a result, she said.

“This time around, one of the great takeaways was that registration was a strength and we had greatly improved efficiencies to reduce registration time,” McFarlan said.

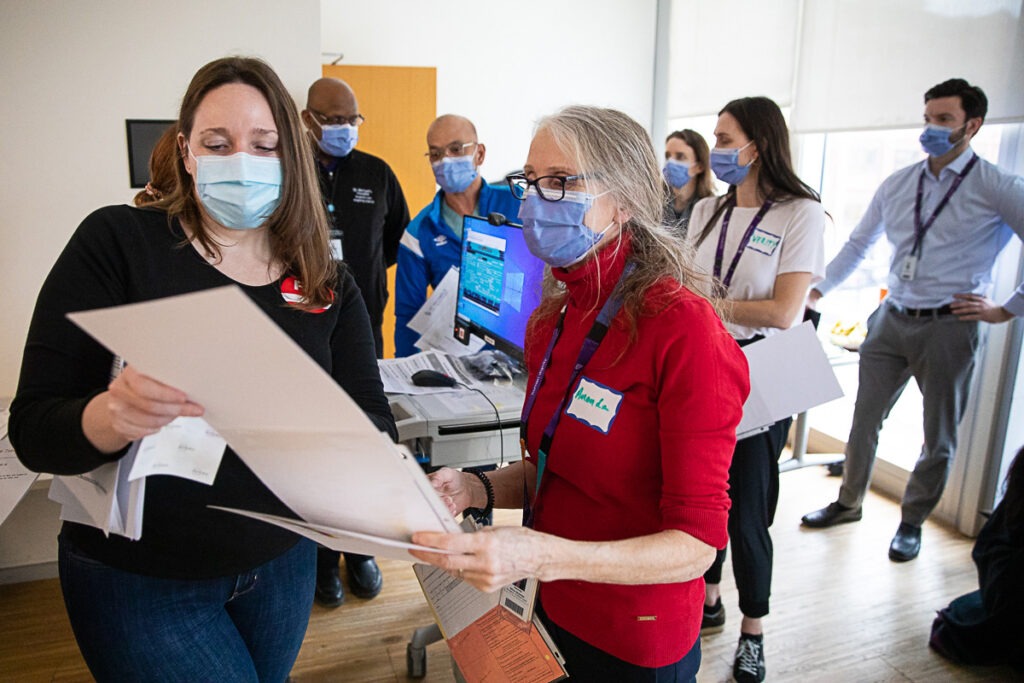

Dry-runs also help staff feel engaged and better prepared, says Quality Improvement Specialist Verity Tulloch.

“The feedback that we received from frontline nurses and clerical staff was that they now feel a lot more confident and ready for when the next Code Orange occurs,” she said.

This feeling extended to staff from other departments, including representatives from Education, Legal, Access and Flow and Surgery, who came to observe the exercise, she said. “We also had responders attend who would be impacted upstream, like the blood bank,” Tulloch said.

Ultimately, these exercises help build relationships between these different groups, which helps build trust in times of urgency, adds McFarlan.

“It builds connections and goodwill and engagement, and recognizes that it’s okay to still have work to do,” she said. “It’s a team sport and everybody’s input is valuable.”

By Marlene Leung

Photos by Eduardo Lima