Lessons from Dr. Alexander Augusta, a Black surgeon who trained in Canada in the 1850s before serving in the Civil War

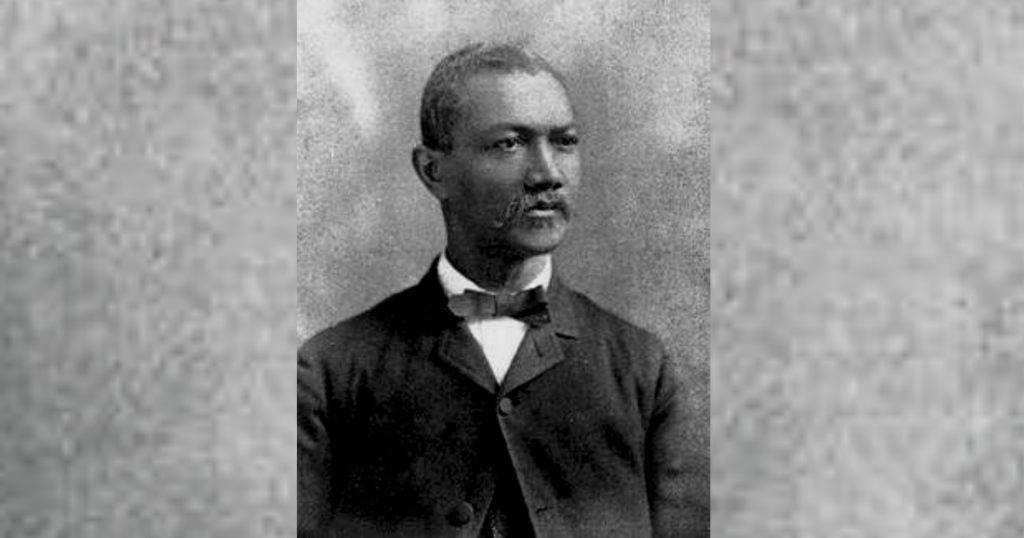

Dr. Alexander Augusta (Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Dr. Alexander Augusta was a Black physician who studied medicine in Toronto in the mid-1800s after being refused admission to medical schools in the United States because of racism. Although he completed his medical training in Canada and practiced for a brief period in Toronto, he returned to America to fight for the Union in the Civil War, becoming the first African-American surgeon in the Union army. He went on to hold many distinguished and groundbreaking positions as a medical educator in the States, and, with full military honours, was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Dr. Nav Persaud, family physician at Unity Health Toronto and Canada Research Chair in Health Justice, recently co-authored a new paper about the remarkable life and career of Dr. Augusta. We spoke with Dr. Persaud bout his interest in researching Augusta’s life in Canada and what his story can teach us about racism and the disparities that exist today in Canadian medicine.

Q: What initially sparked your interest in researching Dr. Alexander Augusta?

Dr. Persaud: It started when I was thinking about how the history of medicine is pretty homogenous and focuses largely on the accomplishments of white men. I wondered if there were other important stories out there that had been overlooked, and that’s when I came across a book by Dr. Heather Butts (who co-authored the paper) that looked at healthcare in the U.S. during the Civil War era. That’s where I learned about Dr. Augusta.

Most of what’s written about him focuses on his time in America. Augusta’s remarkable time in Canada hadn’t been carefully examined, so that’s why we chose to focus on his decade here.

Q: This paper was published in the Canadian Medical Education Journal, why do you feel Augusta’s story is important for medical and healthcare students to know?

Dr. Persaud: Augusta’s experience here in Canada can help us understand the disparities that exist today in Canadian medicine. Even today, medical schools don’t represent the populations that they serve, and if you want to understand why, part of that means going back to Augusta’s time.

Augusta had some pretty good reasons to stay in Canada, he was barred from getting into U.S. medical schools, and people were still being enslaved in the U.S. But he decided to go back to the States and put his life at risk fighting for the Union, rather than staying in Canada. Fighting against the Confederates in the Civil War was obviously very important to him, but things weren’t easy for him here.

During his brief time here, Augusta spoke out against racism and discrimination in Canada. When there was a proposal to create a segregated colony for Black people on Ontario’s Manitoulin Island, he advocated against it, drawing parallels to the American south. He also was president of the Association for the Education of Coloured People in Canada, a group that helped ensure Black children had the necessary supplies and supports to succeed at school. It appears he never worked at a large hospital in Toronto, but after the Civil War he headed a hospital in the United States.

His story counters the very simplistic narrative of America being bad, and Canada being good. Sometimes there is this idea of Canadian exceptionalism in comparison to America, and people assume that racism wasn’t a problem in Canada and isn’t a problem today. Augusta’s life shows that it’s a much-more nuanced story than that. Obviously there was a good reason for him to come here, and racism in America was a big part of that. But there was also good reasons for him to leave Canada, and racism was one of them.

Q: How did you find the historical information to tell Augusta’s story?

Dr. Persaud: It took a long time to pull together the archival information for this paper. It meant working in collaboration with Dr. Butts and Alanna McKnight, a Toronto-based historian. It also meant spending a lot of hours sifting through original documents at the University of Toronto, University Health Network, Ontario and Toronto archives.

In some cases, I was gingerly turning the pages of original paper documents from the mid-1850s, reading every word written in cursive to find mention of the name “Augusta.” I’m a family doctor and I do clinical trials, so this was definitely outside of my routine, but it was also exciting. I remember the thrill of seeing the name “Augusta” in a set of minute meetings. There were a lot of disappointments in doing this research, but that made it even sweeter when I found important documents.

Q: What are some lessons we can learn from Augusta’s story that are relevant today?

Dr. Persaud: He faced racism here in Canada, and the racism that exists here today in healthcare is connected to what he experienced. This same racism explains the relative underrepresentation of Black physicians among faculty members, which in turn affects whether Black people and other racialized people believe they’ll be welcome in the field of medicine.

The other thing that’s inspiring about his story is that he could have selected a relatively more comfortable and easy life in Canada. He could have continued his private practice in Toronto, but he knew people were enslaved in America and he could use his skills for good. He decided at great personal risk to join the Union Army. That’s the really important lesson from his story that’s applicable to today – that racism is not going to just go away with the passing of time. We need to each take action to stop racism. This may involve personal sacrifices — not as great as those made by Augusta – but we all have a role to play.

Based on the records we have, Augusta combined clinical excellence with advocacy and action. I think that can counter this narrative that racism is a special topic that other people are supposed to address. I hope his story might inspire other physicians, healthcare providers and trainees to combine a focus on clinical work with making bigger changes that affect everyone in our profession, our patients and society at large.

-By Marlene Leung. This interview has been edited and condensed.