For 100 years, Black nurses have offered exceptional care and leadership at Unity Health hospitals. Here’s how they challenged the status quo

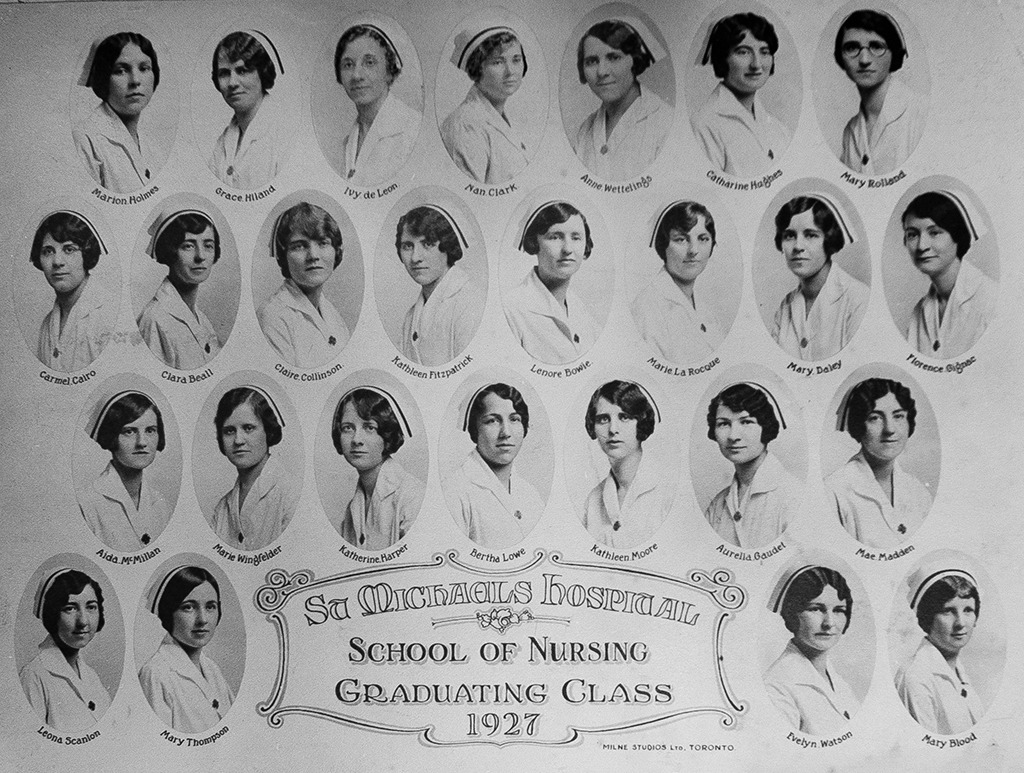

The 1927 graduating class, including Ivy de Leon. (Photo courtesy St. Michael's Archives.)

A century-old black-and-white photo recently uncovered in Unity Health Toronto’s archives reveals a story of strength, resilience and trailblazing – that of Jamaican-born Ivy de Leon, who broke the colour barrier at St. Michael’s Hospital School of Nursing in 1927.

“Generally, people think that the first Black nursing students in Canada graduated in the 1940s,” says Teruko Kishibe, Unity Health archivist and information specialist. “This is the earliest Black nursing student that I know of in Canada.”

Ivy de Leon represents the first in a century of trailblazing Black nurses who followed her. Allison Needham, Director of Anti-Racism, Equity and Social Accountability at Unity Health, says it’s time their stories were heard.

“It’s about our ability as a Catholic organization, when we speak of the Sisters of St. Joseph and the founding of our hospitals, to acknowledge who was there and who wasn’t there,” she says. “It’s time to pivot as an organization to tell stories that are often not told.”

Because such stories are seldom in the official record, it takes effort to find them. For Black History Month, Needham and Unity Health’s Council on Anti-Racism, Equity and Social Accountability (CARESA) launched a project to uncover the history of Black nurses at Unity Health.

They worked with Kishibe, who undertook original research, examining class photos from St. Michael’s School of Nursing, which operated from 1892 to 1974 – when community colleges took over nursing education in Ontario.

When Kishibe dug into that archival trove of St. Michael’s School of Nursing grad photos, she uncovered Ivy de Leon. It took her aback to discover a Black nursing student from Jamaica graduating from any Canadian nursing school, let alone St. Michael’s School of Nursing, in 1927.

“I felt like a treasure hunter,” says Kishibe. “When I saw her name and where she’d come from and then looked at the date, I had to look at it twice.”

While there is no record of de Leon practising nursing after 1927, her graduation from nursing school was an exceptional achievement at a time when Black nursing students were unheard of in Canada. She would remain an exception for decades to come, not only at St. Michael’s Hospital, but across the country due to racist practices.

Black Nurses who attended St. Michael’s Hospital School of Nursing by graduation year

- 1927: Ivy de Leon (Jamaica)

- 1950: Jean Rix (British Guiana, now Guyana)

- 1952: Juliana Onwu (Nigeria)

- 1953: Pearl Clunes (Trinidad)

- 1955: Aldith Farrar-Karram (Jamaica)

- 1957: Joane Cooke (Jamaica)

- 1959: Catherine Dean (Bahamas)

Academic Karen Flynn of the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign writes that until the 1940s, prospective Black nursing students in Canada were told to go American nursing schools, which opened up to Black students as early as the 1870s. (See the reading list at the end of this article to learn more about discrimination against Black nursing students and their fight for acceptance.)

St. Michael’s didn’t accept another Black nursing student until Jean Rix in 1950. Rix was the first in a series of Black students who attended the hospital’s nursing program throughout the 1950s (See Black Nurses at St. Michael’s School of Nursing, at right). Many of these nurses came from the West Indies. It was a trend that would continue into the 1960s and 1970s, when the hospitals in our organization began actively recruiting Black nurses trained in the Caribbean and the U.K.

These nurses had additional training in such specialties as midwifery and psychiatry. In fact, that was a condition of their employment under the Immigration Act at the time. As the Globe and Mail reported in 1960, this condition amounted to discrimination against West Indian nurses. It added a requirement for entry and acceptance that white RNs from other countries did not face.

Canada’s immigration policies may also be one reason hospitals hired West Indian nurses earlier and in greater number than nurses from other groups within the African Diaspora.

Many West Indian nurses who worked at St. Michael’s Hospital, Providence Healthcare and St. Joseph’s Health Centre rose to leadership positions, taking on head nurse roles. (See West Indian nurses at Unity Health in the 1960s and 1970s).

But they still faced overt and structural racism. Judy Allen, a Jamaican-trained RN who came to St. Michael’s Hospital in 1972, recalls a cold reception in Toronto.

“When I came here and I saw people looked at me differently and I thought, Wow. I had never seen that before,” she recalls. “I would go to the bus and say good morning. Nobody answered. They would either put their head down or turn their head away. That’s one of the most dehumanizing things you can do to another human being.”

As a Black nurse, she received a similar reception from patients, some of whom pulled their hands away from her. Some staff members assumed she was a nursing assistant, even though she was dressed in a nurse’s uniform. But she demanded respect from patients, doctors and fellow nurses throughout her career.

She still does, in her role as Reverend Deacon Judy Allen at the Anglican Church of the Holy Family in Brampton, where she offers pastoral care.

“There was always something in me that I felt I could speak,” she says. “My grandma taught me at an early age, never be afraid to speak your truth. When you speak up from a place full of caring and love, people know.”

She applied her compassion and cultural understanding to provide support to patients.

“There were times when some of my colleagues would say to me, ‘I don’t know what this patient is saying.’ And I go in the room and it might be a Black person, West Indian or sometimes an older person and I would say, ‘Good morning, mama, how are you doing? You all right?’ And you could just see they would relax and talk.”

Succeeding generations of West Indian nurses also mentored younger Black nurses like Jacqueline Chen, now Clinical Leader Manager of Primary and Community Care at St. Michael’s Sumac Creek Health Centre and the Wellesley-St. James Town Health Centre. Chen said she had strong, supportive role models, including her own mother, who immigrated from St. Vincent and the Grenadines and worked in a nursing home as a nursing aide for 40 years.

“I was fortunate to have many Black RN mentors when I started my nursing career that wrapped around me and supported me and really instilled the strong nursing foundation that has kept with me all of these years,” she says.

West Indian nurses like Allen inspired Lisa Manswell, an RN at Unity Health, to pursue a career in nursing. Her mother – who immigrated from Trinidad – worked as an occupational therapy assistant at Providence Healthcare. As a young girl, Manswell would follow her mother on her rounds to talk to the elderly patients, and sometimes hold their hands.

“It was that therapeutic touch that really resonated with me,” she said.

When Manswell began her career at St. Michael’s Hospital in 2007, she worked directly with Allen, who was senior nurse in the Day Surgery Unit at the time.

“Judy taught me many skills and valuable lessons of compassion, authenticity and patience, which I hold so dear to my heart and helped to shape my nursing journey,” Manswell says.

Manswell first met Chen while she was in her graduate nursing program. She describes Chen as a “pillar of support” throughout her journey as a Black nurse, both within the hospital and in the community.

“I was inspired by the fact that she is a Black nurse leader in the formal role of Clinical Leader Manager – we only had two at St. Michael’s Hospital at the time,” she says. “I perceive both women as my mentors, and they paved the way, demonstrating the possibilities for Black nurses at Unity Health Toronto and in Canada.”

Winner of the 2020 Unity Health Inclusivity Award, Chen uses compassion and cultural understanding to lead her team of diverse staff. In her many years of service as a Diabetes Educator, she applied her expertise in diabetes management – an expertise she developed to support the Caribbean-Canadian community – to help the South Asian community.

As a leader, she has hired qualified staff at Sumac Creek to reflect the clinic’s population in Regent Park.

“It’s not only about seeing somebody that looks like you, but also having somebody that is able to relate to your experience culturally, like your foods and customs, and come up with strategies that resonate with the individual,” she says. “Culturally relevant care is an important consideration in health care.”

Looking at the next hundred years, Chen says Black nurses need more support from non-Black allies. She notes the powerful and positive impact of white allies in advancing her own career – including a colleague who vouched for Chen becoming a clinical leader manager.

“Unfortunately, it’s very common for racialized people to feel that they’re not good enough to do the job even though they are qualified to do the job,” she says. “One of the ways we can support Black staff, up-and-coming leaders, is to create a forum in which they have allies who are able to vouch for them.”

Manswell hopes to support new generations of Black nurses the way Allen and Chen mentored her.

“My aim is to share what I have learned from them through modelling the way and creating a culture of mentorship and coaching of younger nurses.”

West Indian nurses at Unity Health in the 1960s and 1970s

1961: Rhoda (Anstey) Young (Jamaica); retired July 1994. She became head nurse in 1968 and was a supervisor in the Operating Room from 1969 to 1982 when she was transferred to act as Manager of the Central Supply.

1964: Pam (Daniels) Willock (Antigua). She studied nursing in England at Royal Hampshire County Hospital where she was the only Black woman in her class, and then pursued specialized training in midwifery and psychiatry in the U.K. She was hired at St. Michael’s Hospital in 1964 and in 1971 was appointed head nurse, remaining the position until 1973 when she left to take on a position at Oshawa General Hospital, helping to establish several new nursing units. She published “The Canadian Caribbean Cookbook” in 1996.

1966: Gerry Simpson (Barbados); retired in July 1989. She trained in England, studying midwifery. She worked at Toronto East General from 1963 until she was hired at St. Michael’s in 1966. She spent five years as a staff nurse on the obstetrical floor and was appointed head nurse in 1979.

1972: Rose Kirnon (Montserrat); retired 1992. She trained in England and pursued midwifery. She was hired at St. Michael’s Hospital in 1972, working at the original ICU until 1975. She moved to general medicine in what is now the Shuter Wing. She became head nurse in 1977.

Source: St. Michael’s Hospital Archives and original research by Dr. Peter Kopplin

Reading list

To learn more about the experience of Black nurses in Canada in the past century and their battle against discrimination and racism, here are a selection of some articles and books:

Articles

- Recognizing History of Black Nurses a First Step to Addressing Racism and Discrimination in Nursing

- “Hotel Refuses Negro Nurse”: Gloria Clarke Baylis and the Queen Elizabeth Hotel

- “I’m Glad That Someone is Telling the Nursing Story”

- Beyond the Glass Wall: Black Canadian Nurses

- Recognizing History of Black Nurses, a First Step to Addressing Racism and Discrimination in Nursing

- Black History Month: Six members of U of T Medicine’s community talk about their work, representation

- Hidden figures of nursing: The historical contributions of Black nurses and a narrative for those who are unnamed, undocumented and underrepresented.

- ‘I’ve walked in the room and they’ve asked, “Where’s the real doctor?”‘ – CBC News

Books

- Colour-Coded: A Legal History of Racism in Canada, 1900-1950

- Blacks in Montreal, 1628-1986: An Urban Demography

- No Burden to Carry: Narratives of Black Working Women in Ontario, 1920s-1950s

- Moving Beyond Borders: A History of Black Canadian and Caribbean Women in the Diaspora

By: Laura Boast