The 50th anniversary of Canada’s first successful heart transplant

By Mary Dickie

- EXTENSIVE GALLERY: Photos, news clippings and memories from 50 years ago

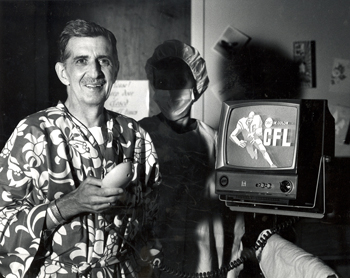

Dr. Clare Baker and his team performed the first successful heart transplant in Canada on Nov. 17, 1968. (St. Michael’s Hospital Archives)

Nov. 17 marks the 50th anniversary of the first successful heart transplant in Canada, performed at St. Michael’s Hospital in 1968 by Dr. Clare Baker and his team. The recipient, 54-year-old Charles Perrin Johnston, lived for more than six years with his new heart.

Dr. Baker, who received the Order of Canada for his work, passed away in 2010, but his widow, Emmaleen Baker, vividly recalls the Sunday night when her husband was called away from the dinner table by a phone call from his St. Michael’s colleague James Yao. The news was good: the team had found a donor heart for their patient, who had been waiting in the hospital for weeks.

At the time there was some friendly competition around which Toronto hospital would be the first to perform a successful transplant.

“The sisters at St. Michael’s were 100 per cent behind Clare doing the surgery,” says Baker, “and I said, ‘Clare, if you feel you’re ready and the sisters want you to go ahead, then go ahead.’ And he did.”

After Dr. John Hart had removed the heart from the donor, an 18-year-old student, the nearly three-hour transplant operation went smoothly. When Dr. Baker returned home early the next morning, “He was more thrilled than exhausted,” Emmaleen recalls. “He was still on a high, because he was so pleased with the way everything turned out.”

Dr. John “J.K.” Wilson was Perrin Johnston’s cardiologist, but he was at a conference in Montreal and couldn’t be present.

“I was on the telephone all night,” recalls Dr. Wilson, who got back 24 hours after the operation to find his patient doing remarkably well, with his vital signs normal.

“The surgery was part one of the treatment,” Dr. Wilson notes. “With transplants, you have to practically live with the patient after the operation for them to survive. We were thinking about him all the time. The first thing we did when we got to the hospital was visit him, and the last thing we did before leaving was look in on him. It’s very difficult work, but we seemed to succeed there.”

Hematologist Dr. Bernadette Garvey was in charge of managing the drugs given to Perrin Johnston to prevent his body from rejecting the new heart.

“Anti-rejection medication had been used for renal transplants, but it was new for hearts,” she says. “Dr. Baker was a man of few words, and once he had done his work he stepped back and let others do theirs without interference. Of course I wanted to monitor the patient very well, but if something were to happen in my area it would be over days, so I just needed to watch him carefully. We were so excited that all went well.”

After South Africa’s Christiaan Barnard performed the world’s first heart transplant in 1967, teams around the world began planning their own transplant surgeries.

“It was such an exciting time,” Dr. Wilson says. “This was new territory, and everyone doing heart surgery was excited about it. And there was a little competition too, like if he can do it, maybe we can do it. Perrin Johnston had been my patient for a couple of years, and when we heard about Barnard doing the transplant, I said to him, ‘Hey, maybe we’ll give you a new heart!’ And it came about.”

Unfortunately, most of the early heart transplant recipients had died soon after their surgeries. “That was the atmosphere that we were working in,” says Dr. Wilson. “So much promise, but still a lot of work to do.”

Charles Perrin Johnston survived longer than any other heart transplant recipient in the world at that time (St. Michael’s Hospital Archives)

As it turned out, Perrin Johnston survived longer than any other heart transplant recipient in the world at that time. His grandson, Lukas Gerber, was too young to remember him well, but he grew up hearing family stories about the transplant, St. Michael’s—where most of his family was born and where his grandmother was head nurse—and Dr. Baker. “My mother said Dr. Baker was almost like a god-among-men character, with a cohort of people trailing after him, hanging on his every word,” Gerber says. “He was just absolutely confident in what he was doing and the way he approached it, and they all fed off that confidence, I think.”

Dr. Baker was born in Saskatchewan and earned his medical degree from the University of Toronto in 1946. In 1953 he became chief of thoracic surgery at St. Michael’s, where he performed vascular, thoracic and closed heart surgery before becoming involved in the new field of open heart surgery.

“Clare was exceptional,” Dr. Wilson says of his colleague. “He was a big man, a tower of strength, and when you looked at him you had confidence. I worked with him for 30 years; we were a team. I was J.K. and he was Baker, so we were known as Jake and Bake.”

“Clare loved teaching in the OR with the senior residents,” recalls Emmaleen. “He found quite a few of them that would have been great surgeons, but they couldn’t deal with losing patients. And in the early days, that’s what happened. People would ask him how he dealt with that, and he’d say, ‘The only way I can do it is to know that I’m not just doing my best, I am doing the best that anyone can do.’”

About St. Michael’s Hospital

St. Michael’s Hospital provides compassionate care to all who enter its doors. The hospital also provides outstanding medical education to future health care professionals in more than 29 academic disciplines. Critical care and trauma, heart disease, neurosurgery, diabetes, cancer care, care of the homeless and global health are among the Hospital’s recognized areas of expertise. Through the Keenan Research Centre and the Li Ka Shing International Healthcare Education Centre, which make up the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, research and education at St. Michael’s Hospital are recognized and make an impact around the world. Founded in 1892, the hospital is fully affiliated with the University of Toronto.

St. Michael’s Hospital with Providence Healthcare and St. Joseph’s Health Centre now operate under one corporate entity as of August 1, 2017. United, the three organizations serve patients, residents and clients across the full spectrum of care, spanning primary care, secondary community care, tertiary and quaternary care services to post-acute through rehabilitation, palliative care and long-term care, while investing in world-class research and education.