Hospitals share medical imaging data to learn how to cut radiation doses

By James Wysotski

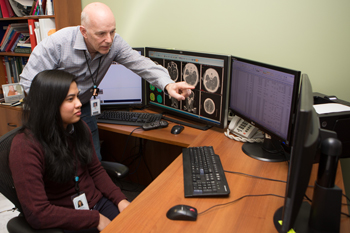

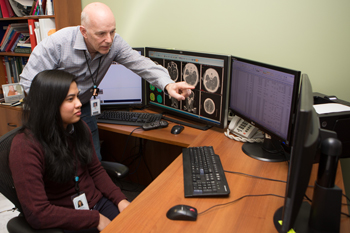

Radiologist Dr. Bruce Gray and data analyst Lianne Concepcion review data submitted to the Medical Imaging Metadata Repository of Ontario. (Photo by Katie Cooper)

Patients might expect radiation doses for medical imaging scans to be comparable from one hospital to the next, but a team at St. Michael’s Hospital said the dose variance can be startling.

In some cases, the machine itself may be emitting higher than needed doses of radiation and in other cases it may be that too many tests were being ordered or the length of the scan too long.

“Some hospitals vary by as much as 40 per cent from the mean average dose for a particular type of scan and its protocol,” said Kate MacGregor, the quality improvement and radiation protection manager in the hospital’s Medical Imaging Department. Protocols are the directions used to carry out the scan while the patient is in the scanner.

She said the variance occurs for several reasons. Some hospitals with newer equipment can scan wider areas faster, which potentially means fewer scans and less radiation. But she said having better equipment doesn’t ensure optimal use. Whether scanners are older or new, improving protocols regarding their use can cut exposure. The key is learning which protocols are best practices and then sharing them between hospitals.

MacGregor is part of a team that is collecting and analyzing data for the Medical Imaging Metadata Repository of Ontario, or MIMRO, to reduce the province’s average radiation dose per scan.

Since the 1990s, MacGregor said the population’s exposure to radiation has doubled, mostly because of increased use of medical imaging, primarily CT. This exposure may lead to an increased risk of cancer by about two per cent annually. She said reducing the number of inappropriate exams and giving doses that are as low as possible may save many patients and families from the heavy burden of cancer.

MIMRO is funded primarily by St. Michael’s and was created by two of its radiologists, Drs. Timothy Dowdell and Bruce Gray. They’re working with a mixture of eight academic and community hospitals that volunteered to submit patient de-identified data from computerized tomography, or CT scans to the registry. The only required identifier is the source hospital’s name so that comparisons can be made after analyzing the data; however, hospital names won’t appear in the any published results since the goal is overall quality improvement.

“There’s no need to stigmatize a hospital that’s already trying to do the right thing,” said MacGregor. “We don’t want a fear of negative findings to prevent other hospitals from participating.”

So far, she said the biggest challenge has been the unstructured nature of the 350,000 CT exams submitted electronically to the registry. Sorting the data to make direct comparisons between hospitals for the same protocol is one of the biggest challenges for the Registry. A number of terms could be used to describe the same protocol or indication for the CT scan: what St. Michael’s called a “routine head exam” might be called a “head with no contrast” at another hospital – and a “routine head” at those places could be a completely different protocol.

“You don’t always need to use the full power of a scanner to find the information you seek. Sometimes a lower dose is enough to find or confirm the intended problem.” – Kate MacGregor |

“When people talk about variations in radiation doses for a protocol, they may not be talking about the same protocol,” said MacGregor.

She said it is data analyst Lianne Concepcion’s task to figure out all of the different names for these protocols so that dosages can be properly compared.

To-date there is no way to use informatics to determine whether or not a CT scan was needed or “appropriate.” This is largely due to the unstructured reporting that is done to report on the scans’ findings. To understand why CT scans are ordered, Concepcion uses statistical programs using natural language processing, an area of computer science that programs computers to process human language. The programs produce lists of keywords that represent all of the terms used to describe a particular indication or reason the scan was ordered.

MacGregor said this process and the one used to sort protocols are incredibly time consuming because the team has to go back to manually check the reports to validate the algorithms’ findings. However, all of this essentially “manual” work leads to finding ways to apply artificial intelligence (AI) to make sense of vast amounts of data that can be collected by MIMRO. By continually feeding this data through the computer software, the machine can learn to sort the protocols and find the clinical indications automatically.

With these lists, MacGregor said the reports from the eight hospitals begin to look like one, common language within Concepcion’s algorithms that analyze the registry data. These algorithms find all of the reports for whatever indication Concepcion seeks.

After four months of programming and testing, MacGregor said the algorithms were strong enough to come up with consistent findings in different sets of data. Now, the team can look at data over time and determine if there are changes in the number of scans done or dosages used. The algorithms can generate comparative results by hospital, scanner type or test ordered.

In a previous study the results from St. Michael’s showed that radiation doses dropped significantly from 2010 to 2014 and have stayed low. One measurement called the “CT dose index volume,” or CTDIvol, dropped 22 per cent. It measures the amount of radiation a scanner emits, so MacGregor said the reduction shows that the hospital’s protocols are effective. Another measurement called the “dose-length product,” or DLP, dropped 13 per cent. It measures the average amount of radiation exposure a patient received during an entire scan. It’s used to determine if scans are done only on relevant portions of the patient’s body, so MacGregor said this reduction shows an improvement in the hospital’s best practices – a process she hopes can be repeated across hospitals within the province.

Each participating hospital will get reports about their dosage rates, said MacGregor. Eventually, they’ll also get a report comparing their rates to the aggregated data of other hospitals. Regardless of the ratings, participants can seek guidance about best practices from other hospitals, and MacGregor said St. Michael’s will play a big role in sharing such information.

MacGregor said best practices are a combination of ensuring that scanners are set to give doses that are as low as reasonably achievable and that hospital protocols prevent inappropriate exams such as repeat scans or overly precise images that use more radiation than necessary. She said the best way to achieve this is to have radiologists work in tandem with medical physicists to get good images at the lowest dose. The physicists who have specific knowledge related to a particular scanner can focus on optimization and quality assurance. Optimization ensures the image quality is maintained while getting the radiation dose to its lowest possible value. She said it takes constant vigilance with practice and process to make a difference, and this is where AI can be applied to increase the safety and effectiveness of CT.

“You don’t always need to use the full power of a scanner to find the information you seek,” said MacGregor. “Sometimes a lower dose is enough to find or confirm the intended problem.”

About St. Michael’s Hospital

St. Michael’s Hospital provides compassionate care to all who enter its doors. The hospital also provides outstanding medical education to future health care professionals in more than 29 academic disciplines. Critical care and trauma, heart disease, neurosurgery, diabetes, cancer care, care of the homeless and global health are among the Hospital’s recognized areas of expertise. Through the Keenan Research Centre and the Li Ka Shing International Healthcare Education Centre, which make up the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, research and education at St. Michael’s Hospital are recognized and make an impact around the world. Founded in 1892, the hospital is fully affiliated with the University of Toronto.

St. Michael’s Hospital with Providence Healthcare and St. Joseph’s Health Centre now operate under one corporate entity as of August 1, 2017. United, the three organizations serve patients, residents and clients across the full spectrum of care, spanning primary care, secondary community care, tertiary and quaternary care services to post-acute through rehabilitation, palliative care and long-term care, while investing in world-class research and education.