Space Kids’ experiment takes science to new heights

By Ana Gajic

Annie Gravely and her team of high school students worked closely with Dr. Jane Batt, scientist at the Keenan Research Centre for Biomedical Science. (Photo by Katie Cooper)

Dr. Jane Batt had always wanted to become an astronaut, but she never imagined a group of high school students would bring her as close as she’d ever come to outer space.

Now a clinician-scientist at the Keenan Research Centre for Biomedical Science, Dr. Batt has been mentoring a team of high school students for four years as they designed and completed an experiment to launch worms to space. Their work studied muscle atrophy in astronauts and compare it to muscle atrophy in people with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease.

Annie Gravely, 16, first approached Dr. Batt with an opportunity to send C. Elegans – a type of roundworm often used to study muscles – into space through the Student Spaceflight Experiments Program (SSEP) offered at her high school, University of Toronto Schools, and facilitated by their science teacher at the time, Ms. Monir.

“My grandfather had ALS,” Gravely said. “In the beginning, this personal connection drove us to find a link between people with ALS and people in outer space.”

Gravely’s core team of high school scientists consisted of Alice Vlasov, 17; Amy Freeman, 21, and Kay Wu, 19. Dr. Batt pointed the team to some other potential mentors in the fields they were interested in.

Working closely with Dr. Batt in the KRCBS Lab; Dr. Peter Roy, a professor at the University of Toronto who specializes in C. Elegans; and Dr. Nathaniel Szewczyk, a professor of space biology at the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom, Gravely and her team put together the experiment.

“The scientific community was unbelievably accepting,” Dr. Batt said. “Having an overseas mentor showed the students that science crosses all borders; it breaks down the differences between us.”

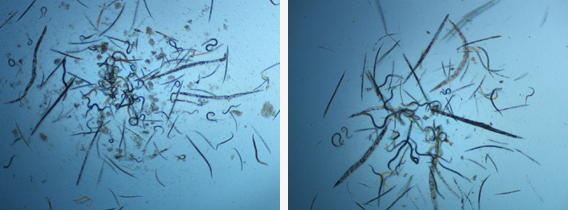

The team of high school students hypothesized that worms exposed to microgravity conditions on the International Space Station would develop muscle atrophy and increased levels of an enzyme called acid sphingomyelinase (ASM) – an enzyme linked to ALS – compared to the worms that remained on earth. No one had ever proven that C. Elegans could survive in space for the length of time they would be gone in the confines of the FME tubes, which are specially designed containers traditionally used for a vast array of experiments in space, and in which the students’ worms had to be housed.

The findings surprised them: after 69 days in space, the space worms returned alive, larger than the control worms, and with decreased levels of ASM. Though their hypothesis was disproven, they had discovered the worms were a viable way to experiment on muscles in space and that they could survive a mission of at least 69 days in FME tubes.

The worms that went to space (left) returned larger and with lower levels of ASM than the worms that remained on earth (right). (Photo courtesy of the Keenan Research Centre for Biomedical Science)

“Our experiment had a lot of limitations because of the nature of space flight,” Vlasov said. “For scientists who have additional resources in the future, we hope our findings act as a stepping stone.”

The team has published their work in the peer-reviewed, academic journal, Gravitational Space Research. With a published paper under their belts before receiving high school diplomas (for Gravely and Vlasov) and post-secondary degrees (For Wu and Freeman), the students have already launched their scientific careers.

“This experience has been really incredible,” said Wu. “I’m still doing research work right now. Staying curious and asking questions – I want to integrate that into my life in some way.”

The team of young scientists — (l to r) Gravely, Wu and Vlasov. Not pictured is Amy Freeman. — now has a published paper under their belts. (Photo by Katie Cooper)

Not only did the ‘space kids’ – as they had lovingly become known in the KRCBS lab – bring Dr. Batt one step closer to space, but they also served as an important reminder.

“As in any profession, scientists can get a little jaded sometimes,” she said. “Working with these students was just about the pure joy of discovery and I had lost some of that along the way. They re-infused that excitement.

“You have to go back to why you really like to do this. You go into scientific research because you have a thirst for knowledge, and these kids have it in spades.”

About St. Michael’s Hospital

St. Michael’s Hospital provides compassionate care to all who enter its doors. The hospital also provides outstanding medical education to future health care professionals in more than 29 academic disciplines. Critical care and trauma, heart disease, neurosurgery, diabetes, cancer care, care of the homeless and global health are among the Hospital’s recognized areas of expertise. Through the Keenan Research Centre and the Li Ka Shing International Healthcare Education Centre, which make up the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, research and education at St. Michael’s Hospital are recognized and make an impact around the world. Founded in 1892, the hospital is fully affiliated with the University of Toronto.