These pediatric health experts are using TikTok to help parents in 10 different languages

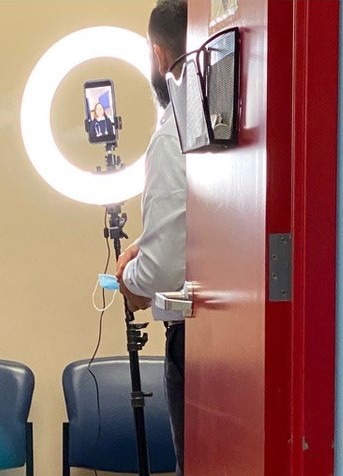

(Photo: Paul Bassi at Beesley Photos)

At a time when children’s health-care providers are overrun with high volumes, many parents have found themselves searching for a reliable and accessible forum for health information online in the middle of the night.

A group of St. Michael’s Hospital family doctors, pediatricians, behaviour therapists and other health specialists have created that resource in 10 languages ranging from Punjabi, to Inuktitut, to Mandarin.

Our Kids’ Health is a multi-channel, multi-lingual social media-based research project with more than 100,000 followers around the world and millions of interactions online. With support from the WHO and others, the network reflects the largest cultural linguistic population groups across Canada based on Census data, with a focus on Black, Indigenous, People of Colour, and historically marginalized populations. Channels are dedicated to Arabic, Black, Cantonese, Filipino, Hispanic, Inuit, Mandarin, Punjabi, Tamil, and Ukrainian kids and their families.

Some videos and reels have garnered more than half a million views. A “You Ask Us” segment that allows parents to pose and receive answers from the Our Kids’ Health experts to questions most pertinent to them has taken off.

“The simplicity of it is part of the key to what’s really resonated with people. It’s accessible. It’s bite-sized,” said Dr. Ripudaman Minhas, a pediatrician and scientist at St. Michael’s who is leading the work. “Research shows that when we receive clinical information from someone who shares lived experience with us, we are more likely to take in health information and apply it to our health behaviours. We’ve translated that into a virtual space.”

Our Kids’ Health started as a social media account to combat the spread of health misinformation for Punjabi families during the pandemic.

“Many approaches used to communicate health information early on in the pandemic were very Eurocentric,” said Minhas. “We came up with Punjabi Kids’ Health to create, translate and adapt the content, delivering it on-screen from professionals who have lived experience and reflect the intended community.”

With the success of Punjabi Kids’ Health as a pilot chapter, Minhas and his research group launched the full network last month. In the reels, health care providers offer tips and advice in different languages and cultural contexts on topics ranging from how to stop a nosebleed to when it’s appropriate to give children cough syrup.

In addition to recruiting health and research professionals to run the channels and adapt content so that it resonates with each cultural group, the team will evaluate the approach using research methods to understand its impact.

“We’re trying to see if creating an online community like this for caregivers from diverse backgrounds impacts their feelings of empowerment, their mental health and stress,” Minhas said. “We’re also interested in seeing how diverse communities use social media in the context of health information. Long term, we want to know whether this may impact how communities navigate the health care system and in turn how it impacts their health status.”

While some may argue social media engagement is beyond the scope of a pediatrician’s work, Minhas disagrees. For many families, social media has become a primary source of health information, particularly in times of isolation.

“This is a really important space for health-care providers to think about how they can advocate, what our responsibility is to try to battle missing and misguided information, and bring evidence-based health information to families in a way that’s accessible,” Minhas said.

It has also been a way to address health concerns for entire families and share information about topics some communities are just beginning to explore. With Punjabi Kids’ Health, Minhas and his team broached subjects such as pregnancy loss, gender identity, and diversity in sexual orientation. They hope to continue this with the new channels to support these important conversations.

In the new year, the team aims to launch a website to categorize and archive information they share so it doesn’t live only on social platforms that can be hard to search.

Ultimately, Minhas says success will only be possible if the Our Kids’ Health teams continue to take the cues from the communities and follow their lead.

“Our channels aim to honour the individual priorities, perspectives, experiences of each cultural linguistic community,” Minhas said. “Using a one-size-fits all approach to health communication leaves communities behind. As our slogan points out, this work is run by our community for our community.”

By: Ana Gajic